CHARBONNEAU: Wilson-Raybould — a uniquely Canadian scandal

A SCANDAL IN BRITAIN brought down the Conservative government in 1963 when it was revealed that model and nightclub dancer Christine Keeler had slept with British and Russian officials. Revelations of the previously well-hidden world of sex- and alcohol-fuelled orgies among Britain’s political elite rocked the establishment.

The walking, breathing, American scandal involves President Donald Trump groping women, mocking disabled people and provoking attacks on blacks. His former lawyer Michael Cohen says: “He is a racist. He is a conman. He is a cheat.” Cohen testified that Trump wanted him to pay off adult-film actress Stormy Daniels who says Trump had an affair with her.

Canada’s scandal is not like that.

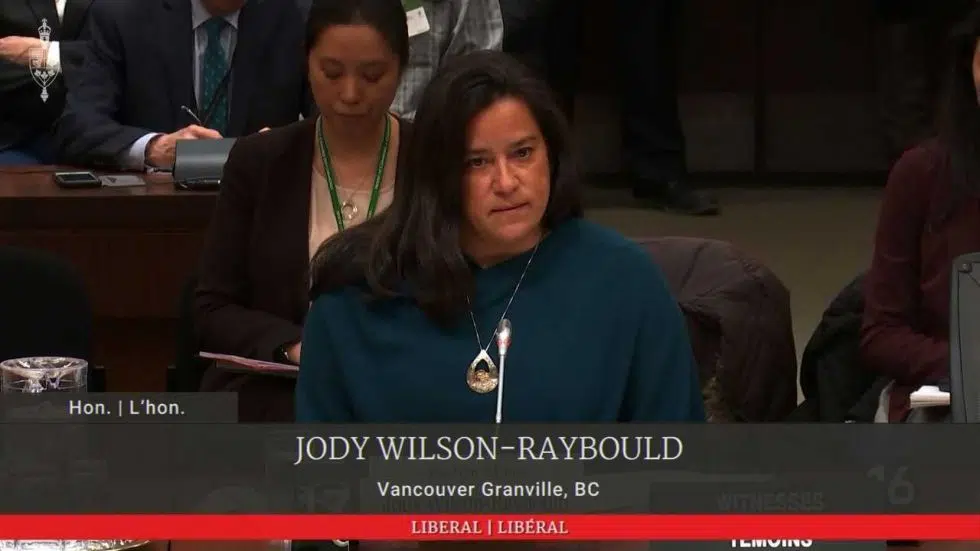

Prime Minister Trudeau is accused of trying to influence Jody Wilson-Raybould to settle a case out of court in order to save thousands jobs. The former attorney general and minister of justice objected to the pressure, especially when she had already decided to proceed with the court case.