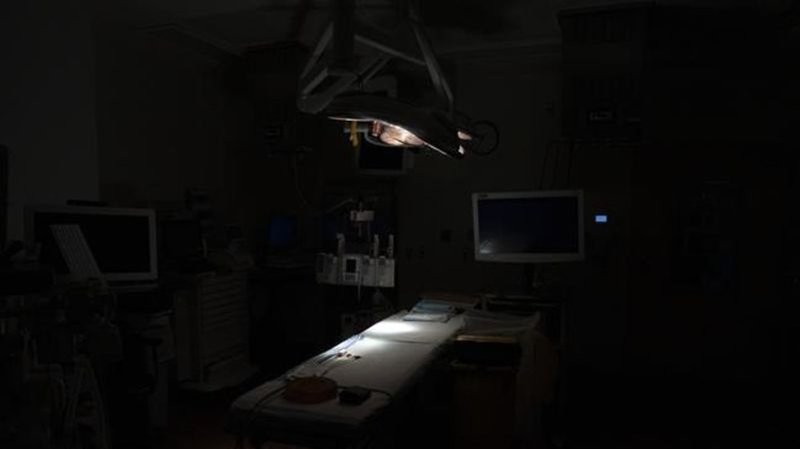

Inside SickKids: As the operating room sits quiet, staff worry about growing backlog

TORONTO — Three large television screens in the nerve centre of the operating room at Canada’s largest pediatric hospital display a list of its surgical spaces, showing which ones have children undergoing procedures at the moment.

There are a lot of blank spots.

Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children usually runs its operating room at 100 per cent capacity. But on this day, six of its 16 surgical spaces are quiet.

That’s after a massive wave of children with respiratory illnesses flooded the emergency department and overwhelmed the intensive care unit, prompting hospital leadership to make the decision in mid-November to cancel many surgeries.