Office highrise elevators COVID pinch point; long line-ups and delays feared

TORONTO — As tens of thousands of Canadian workers start preparing for a post-lockdown return to their offices, elevators have become a hot-button issue amid concerns about the potential for long line ups and frustrating waits to get up or down.

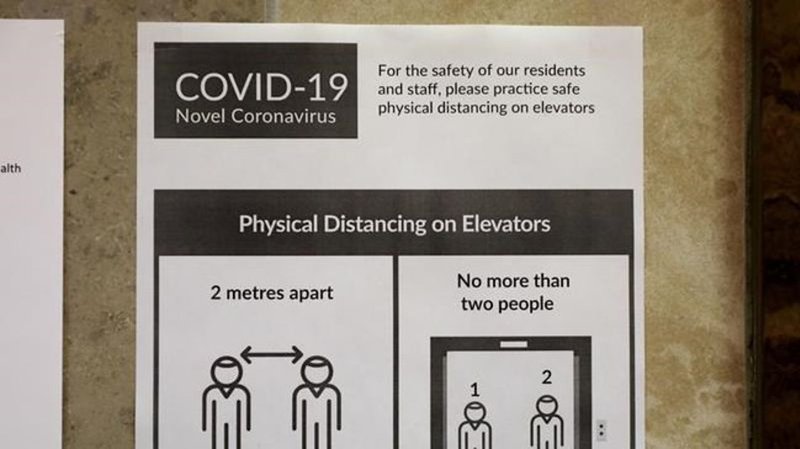

Highrise building operators in particular are trying to figure out how to ensure people can get to their office floors while maintaining adequate physical distancing recommended by health authorities to curb the spread of COVID-19.

While offices can be modified to ensure people keep sufficiently apart, getting them safely inside once they start coming back presents its own unique challenges.

“You never think of elevators as the pinch point of a building, but now, because of what we’re trying to do, it really becomes apparent that it is,” said Ron Isabelle, an engineer and longtime elevator consultant. “Elevators are becoming the bottle neck in the building.”