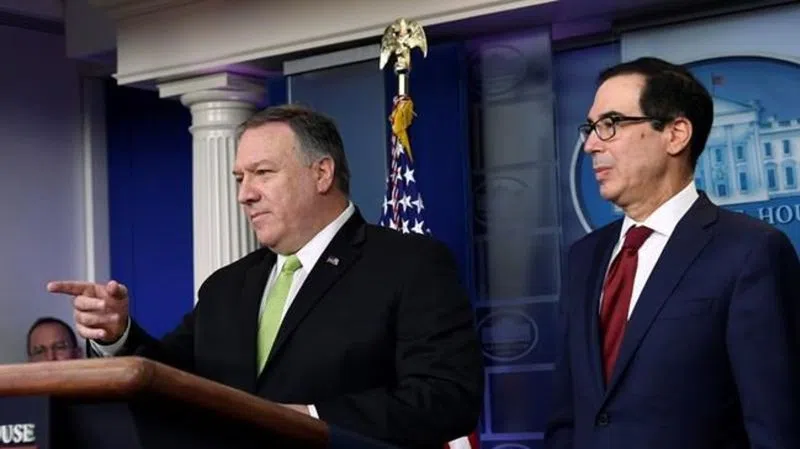

Pompeo, Mnuchin defend sanctions strategy in Iran as they detail latest measures

WASHINGTON — The United States launched an economic counterattack Friday in its high-stakes standoff with Iran — a modest response likely owing to the lack of American casualties in Iranian missile strikes and the crash of an airliner allegedly shot down outside Tehran, but yet another wedge in the relationship between the West and a global pariah known for harbouring dangerous ambitions.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin announced an array of fresh sanctions against eight senior security and military officials in Iran, as well as several of the country’s industries, including textiles, manufacturing, mining and the steel and iron sectors.

Pompeo made a point of contrasting President Donald Trump’s approach with that of the Obama administration, which he accused of opening up “revenue streams for Iran” — a reference to the previous government’s easing of sanctions as part of the international 2014 deal aimed at curbing the country’s nuclear ambitions.

“Under our administration, oil revenues are down by 80 per cent and Iran cannot access roughly 90 per cent of its foreign-currency reserves,” Pompeo said. Iran’s own president, Hassan Rouhani, recently conceded the country has lost more than US$200 billion in foreign income and investment, he added.