50 years on, allegations at root of Sir George Williams riot forgotten

MONTREAL — Fifty years after what became known as the Sir George Williams riot, one of the students whose allegations of racism triggered the explosive events says it’s a shame they were never able to receive a fair hearing.

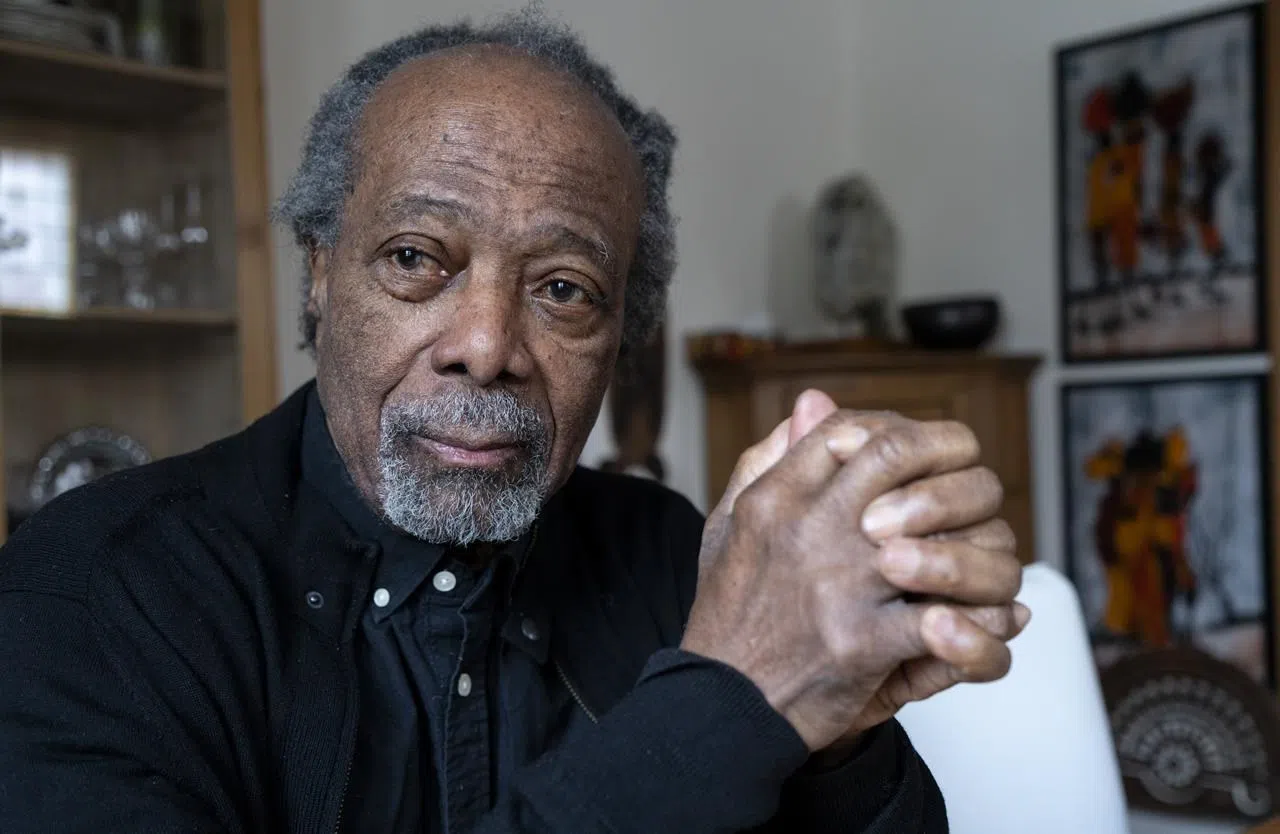

Rodney John was one of six black biology students at Montreal’s Sir George Williams University who accused a professor of discrimination. A sit-in that began Jan. 29, 1969 ended with a riot and fire the following month.

John, now 77 and living in Toronto, says he is comforted that the events are still being talked about 50 years later, but he fears the focus is too much on the occupation and not enough on the initial grievances.

“Because what actually is the matter is that the general public’s awareness of the issues goes back to the occupation — what is lost is that our stories were not told,” he said in an interview.