‘I proved my innocence.’ Glen Assoun cleared of murder after 17 years in prison

HALIFAX — A Nova Scotia man who served 17 years in prison for murder was acquitted of the charge Friday after a two-decade struggle to prove he was wrongfully convicted of fatally stabbing his ex-girlfriend.

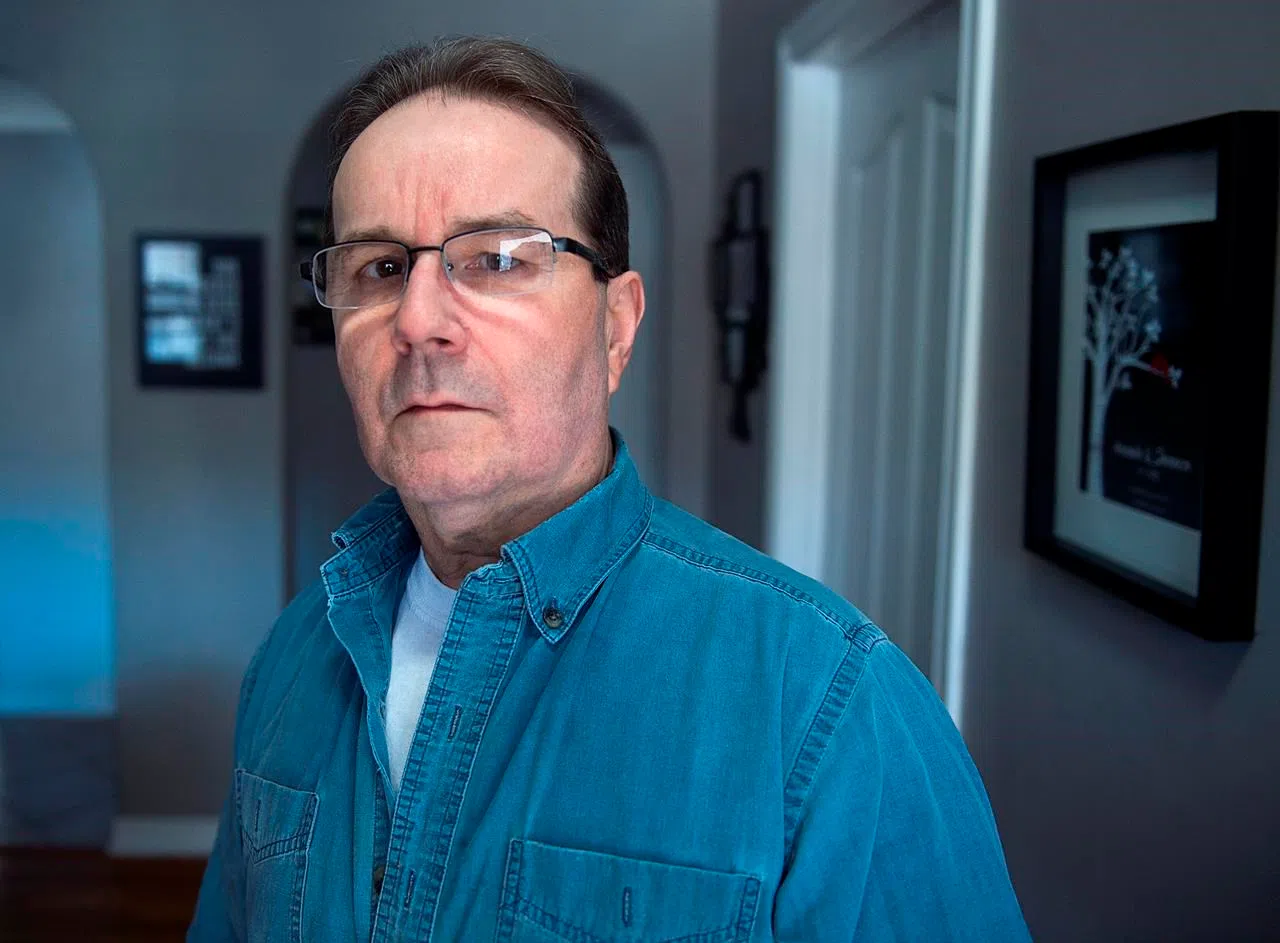

“I proved my innocence here today, after 21 years,” Glen Assoun said as he emerged from a Halifax courtroom.

“I never gave up hope. I knew this day would come. I just didn’t know when.”

Inside the courtroom, his two daughters cried quietly as the Crown dropped the case, effectively exonerating the 63-year-old in the 1995 murder of Brenda LeAnne Way.