Calgary sport school that grooms Olympic champions threatened with shutdown

CALGARY — The National Sport School in Calgary that produces Olympic and Paralympic champions faces possible closure after a quarter century.

The Calgary Olympic Development Association — now WinSport — and the Calgary Board of Education jointly established the school in 1994 to help athletes both pursue sport at a world level and graduate from high school.

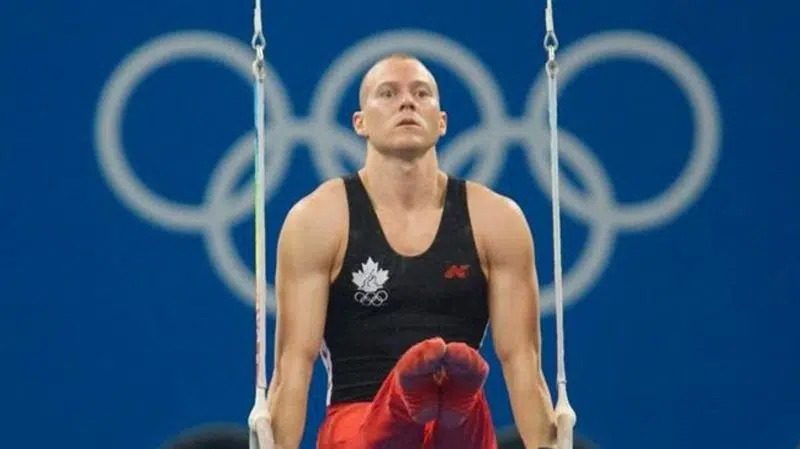

Alumni include Olympic champions Kyle Shewfelt (gymnastics), Jennifer Botterill, Carla MacLeod and Jocelyne Larocque (hockey), Kaillie Humphries (bobsled), Brady Leman (ski cross) and six-time Paralympic swim champion Jessica Sloan.

Two dozen NSS alum competed in the 2018 Winter Olympics.