Facing humiliating controls, Lebanese focus fury on banks

BEIRUT — Before picking up cash from a downtown bank in Lebanon’s capital, Mey Al Sayegh mentally braces herself for what would have been a routine trip before the country’s crippling cash crunch.

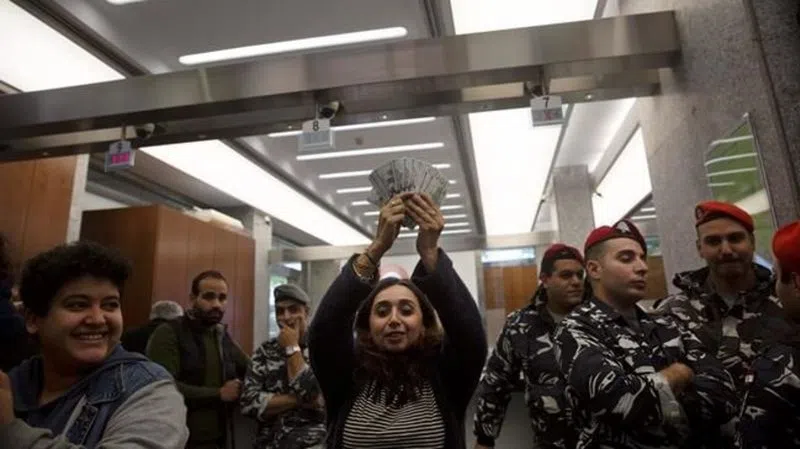

For starters, it will be at least an hour’s wait in line before her turn comes. And if she’s lucky, she’ll be able to withdraw $300 — the weekly limit on dollar withdrawals imposed by banks to preserve liquidity — without having to bargain with the teller.

“I tell my family ‘I’m going to the bank, but I don’t know when I’ll return,'” said the communications manager. “It’s very unpleasant. You see people’s expression — worried, confused, they’re scared that they’re going to lose their deposits.”

For years, many Lebanese have lived beyond their means, supporting their out-sized spending with loans and generous remittances from diaspora relatives scattered across the globe, including family members working in oil-rich Arab Gulf countries.