Young Canadians say current events, string of bad news adding to anxiety

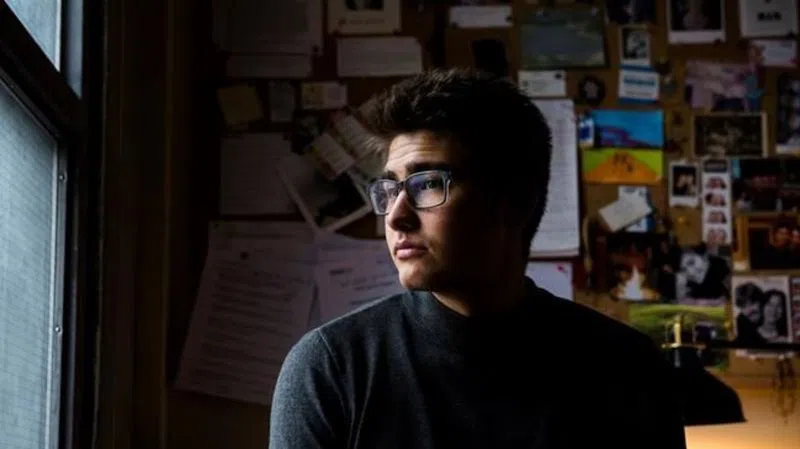

Anxiety and apathy have both come easily to Galen Watts so far this year.

The PhD student at Queen’s University has watched with a mix of dismay and detachment as headlines about rampant wildfires in Australia and the threat of imminent war between the United States and Iran flooded his screens. The bad news intensified last week, with word that the American-Iranian tensions had escalated to include a missile attack targeting U.S forces in Iraq and hours later a deadly plane crash near Tehran that killed 176 people, including at least 57 Canadians.

But Watts’ reactions to the bleak headlines felt muted after three years of dramatic emotional shifts between resignation and outright fear.

Watts, 30, said the latest raft of troubling global headlines marks another ride on the seesaw he and many of his fellow millennials feel they’re riding. The constant barrage of bad news and urgent commentary, he said, has left him questioning the validity of his emotional reactions.