Family of Kamloops man who died in RCMP cells calls for different approach to public intoxication

KAMLOOPS — The family of a man who died in Kamloops RCMP cells is calling for a different approach to public intoxication issues.

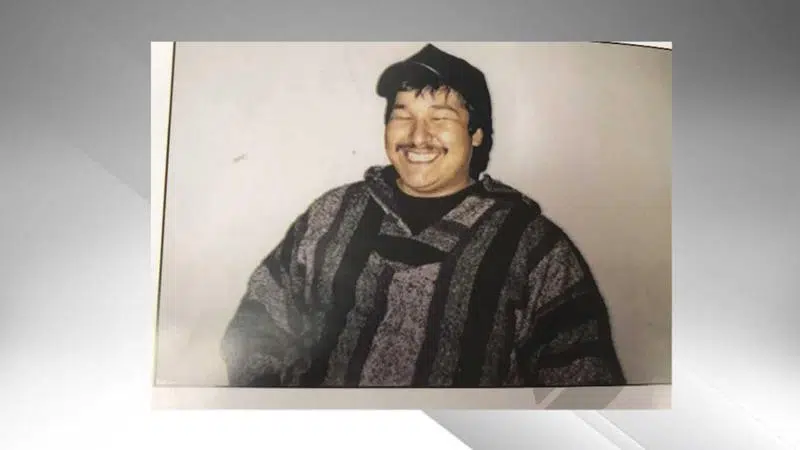

Lenora Starr is the sister-in-law of 49-year-old Randy Lampreau, who was found dead in his jail cell this past March.

After being presented with the results of an investigation into his death yesterday (July 25), Starr and the rest of Lampreau’s family say they will continue to push for system change.

A BC Coroners Service reported concluded the cause of death was inflammation of the heart muscles. Methamphetamine toxicity was also reported as a significant factor in Lampreau’s death.