US agency seeks ‘hosts’ for rotting whales amid die-off

PORTLAND, Ore. — So many gray whales are dying off the U.S. West Coast that scientists and volunteers dealing with the putrid carcasses have an urgent request for coastal residents: Lend us your private beaches so these ocean giants can rot in peace.

The number of dead whales washing ashore in Washington state alone — 29 as of this week — means almost every isolated public beach has been used. Authorities are now scrambling to find remote stretches of sand that are privately owned, with proprietors who don’t mind hosting a rotting creature that’s bigger than a school bus and has a stench to match its size.

“The preferred option is, at all times, that they just be allowed to decompose naturally,” said John Calambokidis, a research biologist with the Olympia, Washington-based Cascadia Research. “But it gets harder and harder to find locations where they can rot without creating a problem. This is a new wrinkle.”

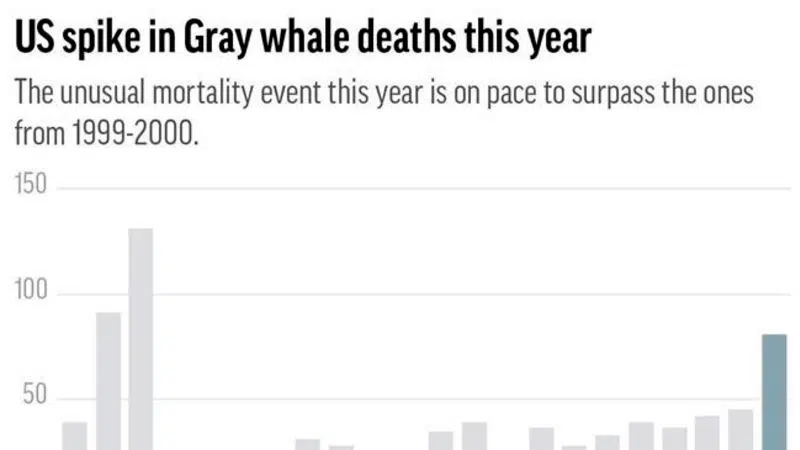

At least 81 gray whale corpses have washed ashore in California, Oregon, Washington and Alaska since Jan. 1. If tallies from Mexico and Canada are added, the number of stranded gray whales reaches about 160 and counting, said Michael Milstein, spokesman for NOAA Fisheries.