Chief military judge’s court martial in limbo after deputy recuses himself

OTTAWA — The court martial for Canada’s chief military judge is in limbo after the judge overseeing the trial — who happens to be deputy to the accused — agreed not to hear the case over conflict-of-interest concerns.

Lt.-Col. Louis-Vincent d’Auteuil also outlined the reasons why he felt the military’s other three sitting judges would not be able to preside over Col. Mario Dutil’s trial in an impartial manner.

That has left the fate of Dutil’s court martial, seen by some as a critical test for the military-justice system, up in the air.

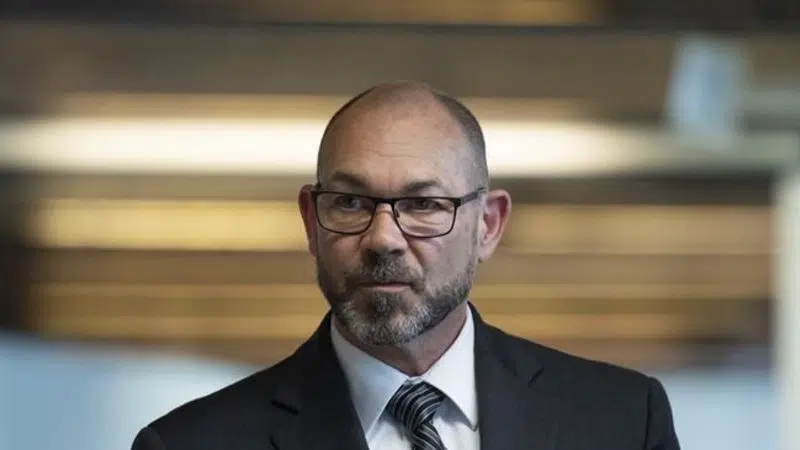

“I met briefly with the prosecutors and asked them to inform me formally as to what the intent is,” Dutil’s lawyer, Philippe-Luc Boutin, said Tuesday. “So I don’t know. We’re just in limbo and waiting for the prosecution to make a decision.”