A Pocket Guide To Sumatran Magic

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

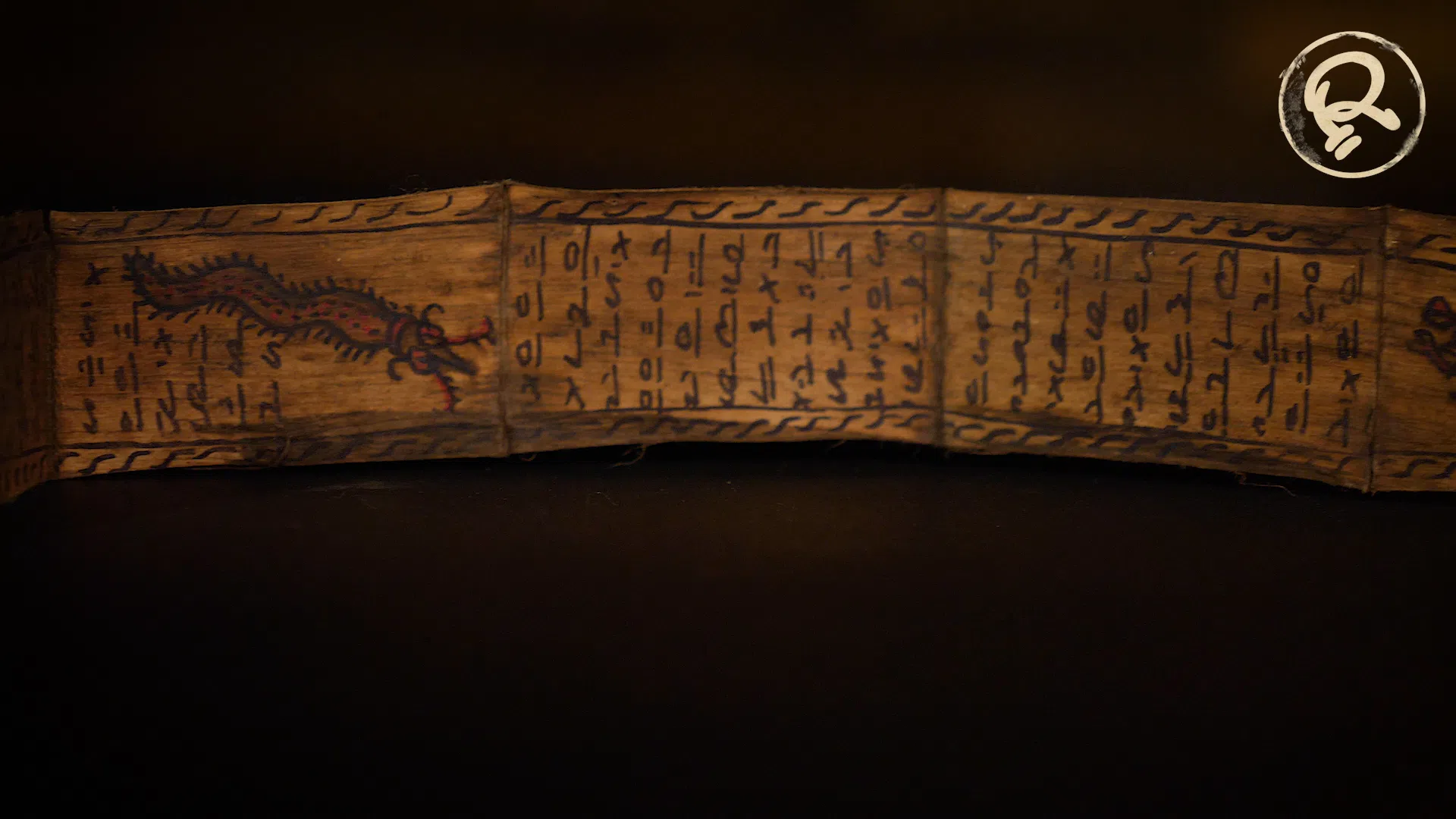

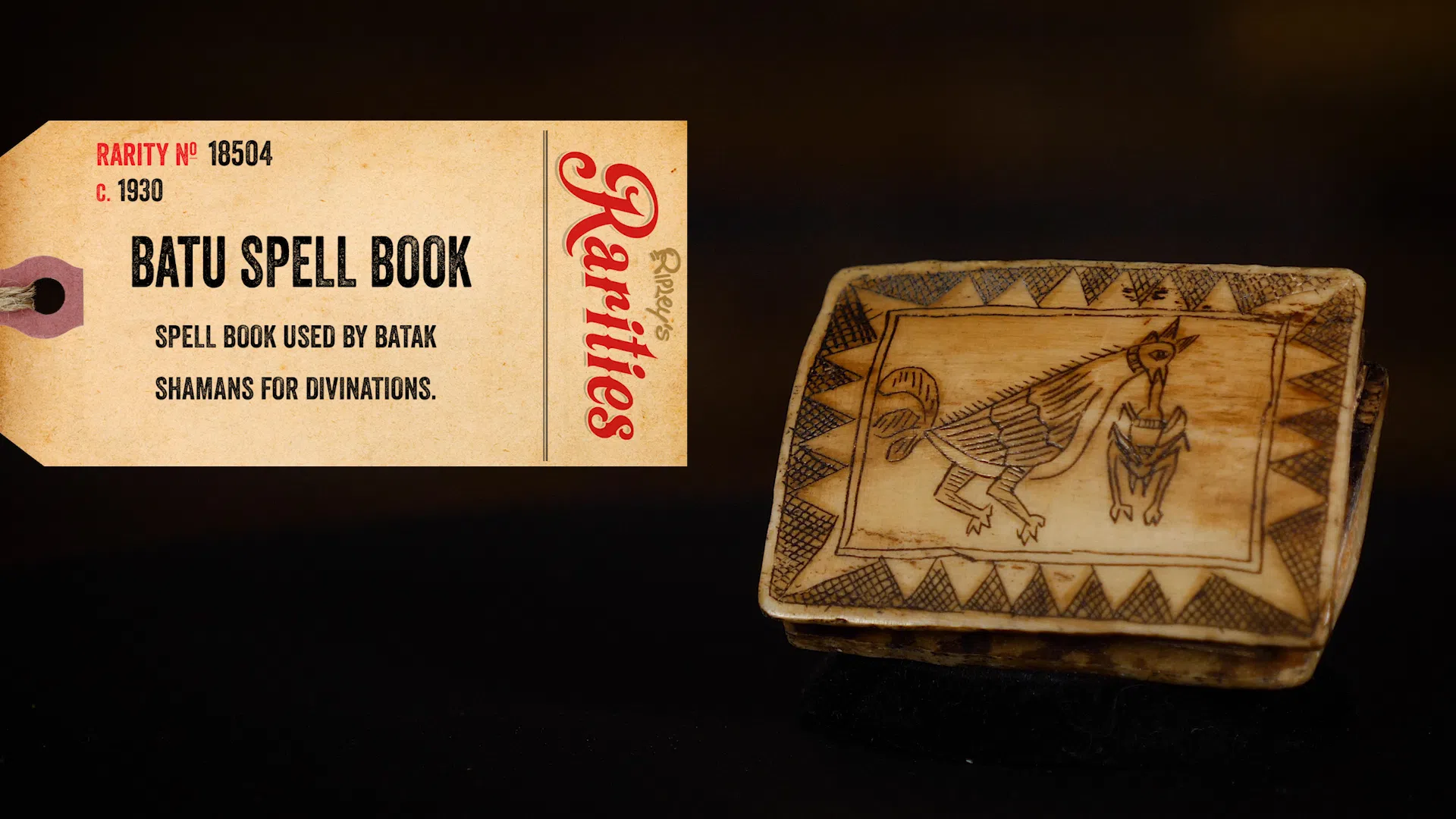

Ritual books known as pustaha were the notes written by Batak shamans learning the sacred mystical arts of their people. Typically written on tree bark with plant resin, these small books contained the notes a priest needed to perform the complex rituals associated with their station.