Indian Act to blame for pipeline gridlock in northern B.C.: federal minister

VANCOUVER — Canada’s minister of Crown-Indigenous relations is pointing her finger at the Indian Act for creating a gridlock in northern British Columbia where some hereditary clan chiefs say a liquefied natural gas pipeline doesn’t have their consent.

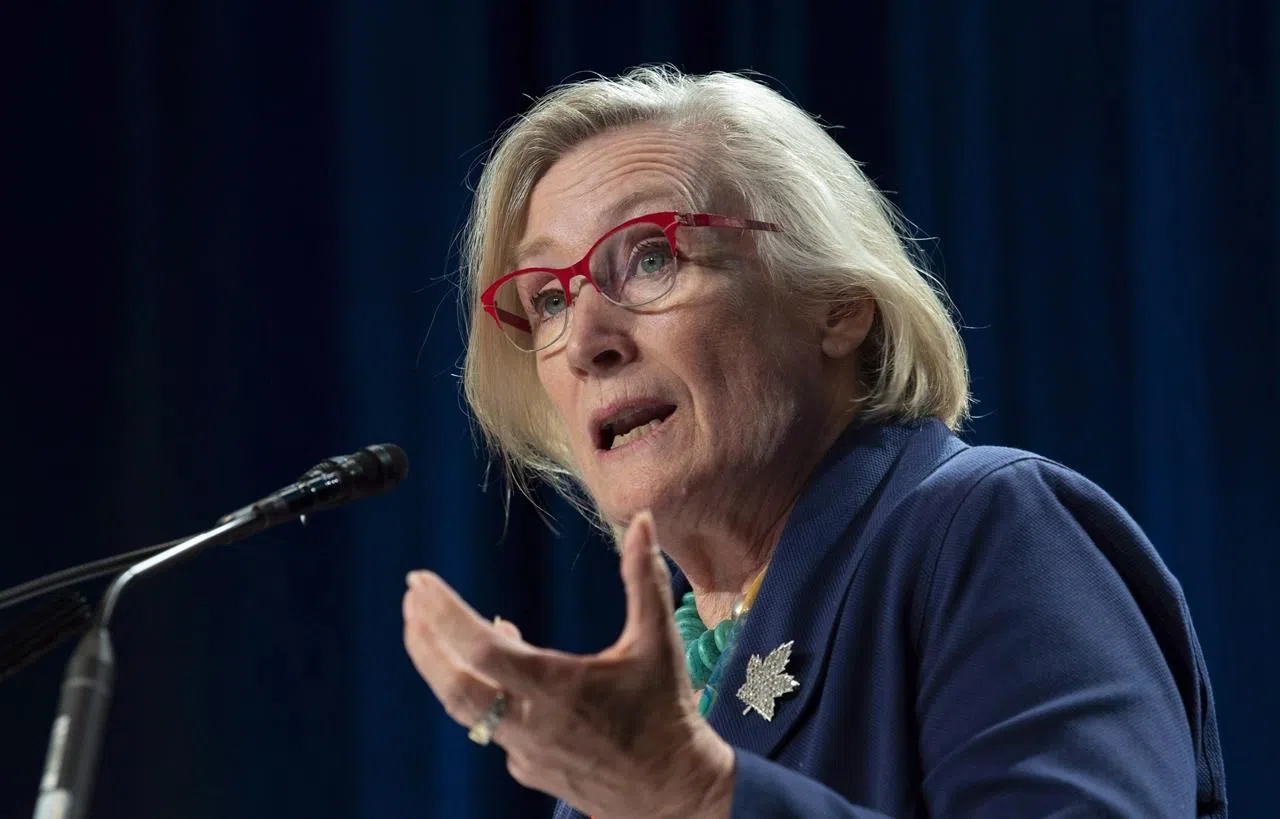

Carolyn Bennett would not say whether she believes the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation have jurisdiction over the 22,000 square kilometres they claim as their traditional territory, saying that it is up to each community to determine its leadership structure.

But she says the situation is an example of why the federal government is working to increase First Nations capacity for self-governance, including a new funding program to rebuild hereditary structures.

“I think that we’re in this transition, hopefully transformation, to be able to get more and more communities out from under the Indian Act so that there isn’t this question of who speaks for the community, as they choose a governance of their own making,” she says.