They’ve got us over a barrel

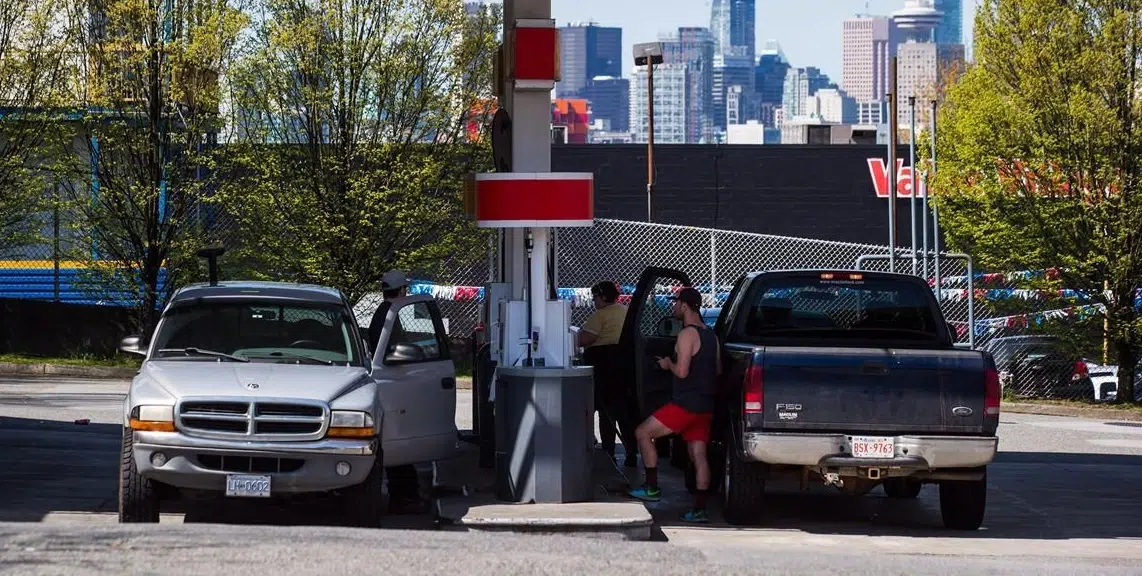

Have you ever wondered how to get the attention of gas retailers such as Petro Can, Chevron or others? I have, and if coffee shop conversations are any indicator, so too have many of you.

The price of gasoline at the pump has been ridiculously high and no, it has nothing to do with the pipeline and Alberta’s little hissy fit over BC wanting the court to rule on jurisdictional issues. In fact, depending on who you want to believe, the retail price has been impacted by refinery shutdowns for maintenance, worldwide shortages, switchover to summer grade gas, demand or any other story being spun by the oil companies and petro-states. However, the one-thing oil companies seldom blame is the cost they are paying for a barrel of oil. It’s something they don’t seem to mention all that often and that omission is in it self a bit odd.

Inventory cost should be a major component in determining retail price. The spread between product cost and retail price is what many refer to as gross margin, yet I now get a sense that oil companies are defining their spread differently. I think they have left economics out of it and have quickly and efficiently moved into an area more commonly known as gouging.

If true, they do it with the full knowledge that we really don’t have much in the way of a choice. If you need your vehicle then you have to come to them and pay the price they demand. And through a quirk of fate, they all seem to demand exactly the same price at exactly the same time. They have us over a barrel. Or do they?