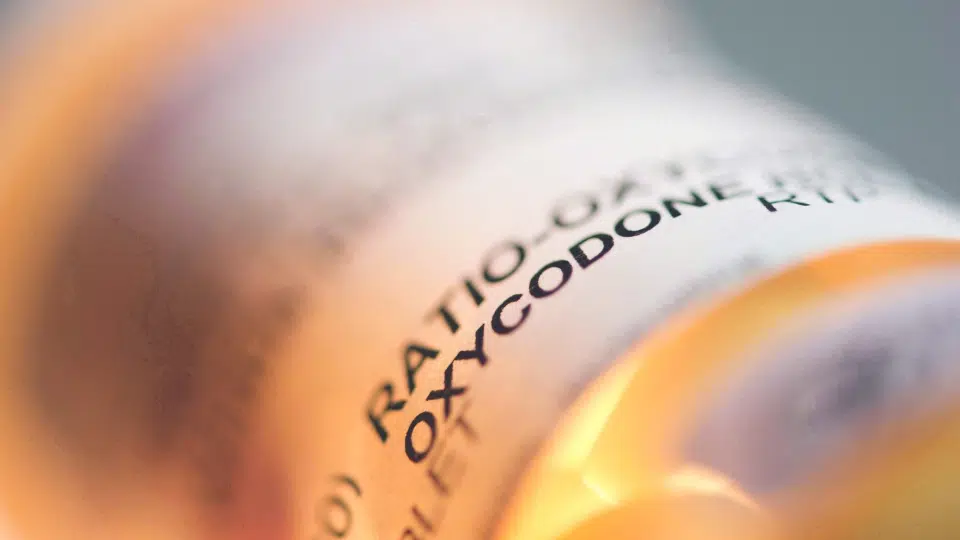

Opioid use rises despite crisis

KAMLOOPS — Am I the only one not surprised that the opioid crisis has worsened? Despite the widespread distribution of naloxone kits to save lives from fentanyl overdose. Despite increased prescriptions of methadone to treat addiction.

It’s all so predictable. The fuse to the opioid bomb was lit long ago.

I just finished reading Dan Malleck’s thoroughly researched book When Good Drugs Go Bad: Opium, Medicine, and the Origins of Canada’s Drug Laws. He traces the opioid crisis that gripped young Canada at the turn of the twentieth century and led to the Opium Act of 1908.

As now, the problem wasn’t the “recreational” use of opium, but rather the prescribed and drug store concoctions of opium. Laudanum, a tincture of opium, was commonly found in medicine chests to treat toothaches and diarrhea, and as a cough suppressant.