B.C. ombudsman says health firings were wrong, wants to close ‘dark chapter’

VICTORIA — British Columbia’s ombudsman says seven government health workers and a contract employee who were fired five years ago because of a flawed and rushed investigation did not deserve the personal, financial and professional harm they suffered.

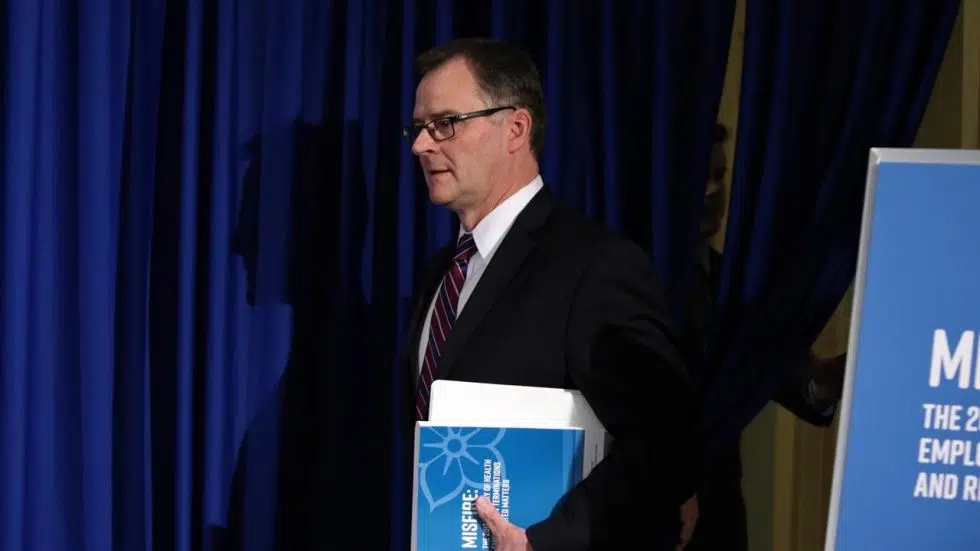

Jay Chalke’s report, called “Misfire,” concluded key decision makers acted on incorrect information to support the decision to fire the workers.

Roderick MacIsaac, a co-op research student working at the Health Ministry, died by suicide about four months after being fired on the grounds he jeopardized the privacy of British Columbians and the reputation of the ministry.

“Mr. MacIsaac’s death was a tragedy that has cast a dark shadow over the entire affair,” Chalke told a news conference.