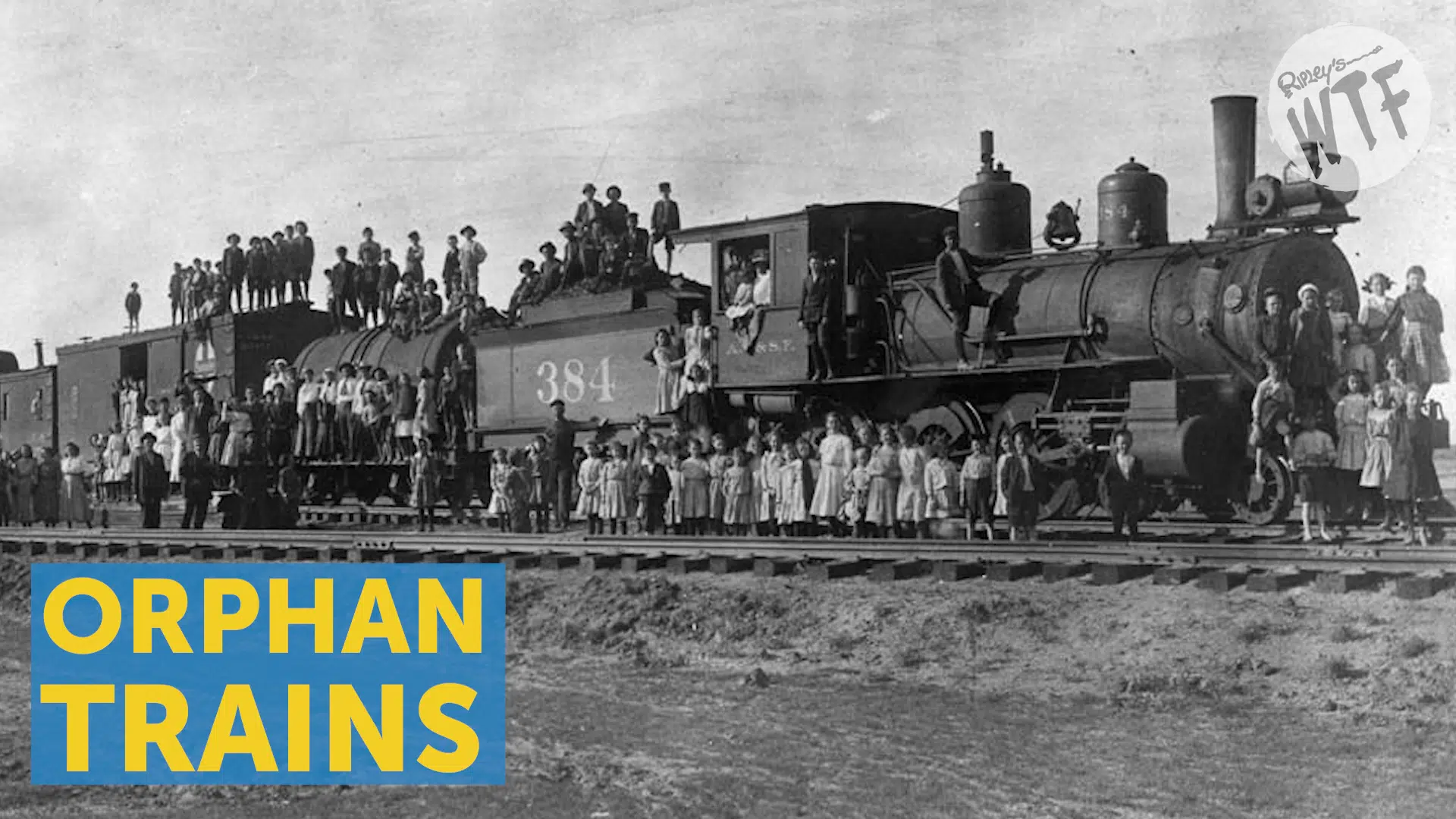

The Orphan Trains Of 19th-Century America

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

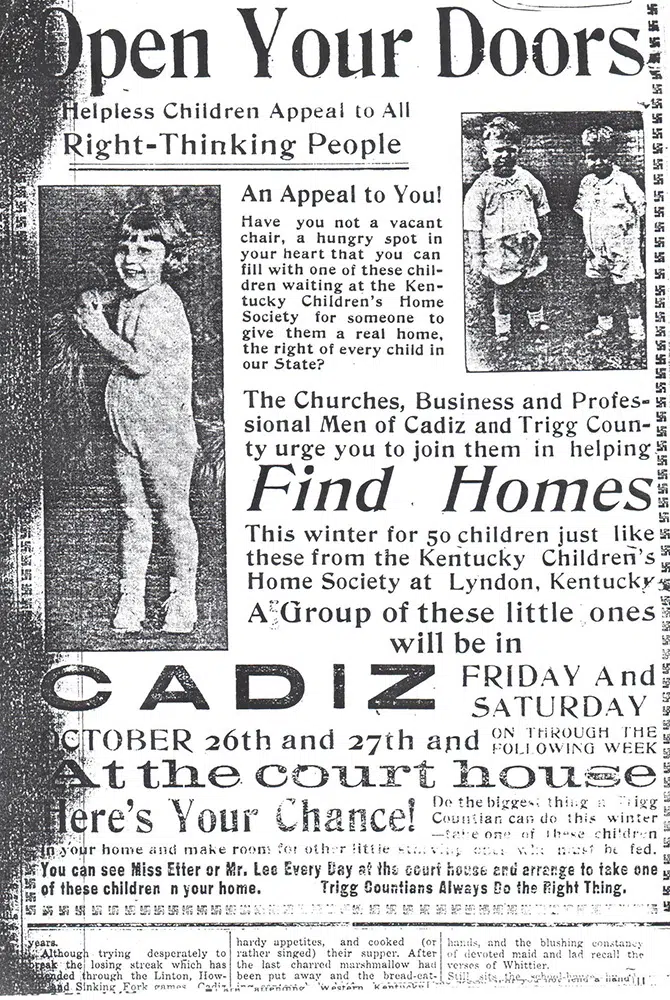

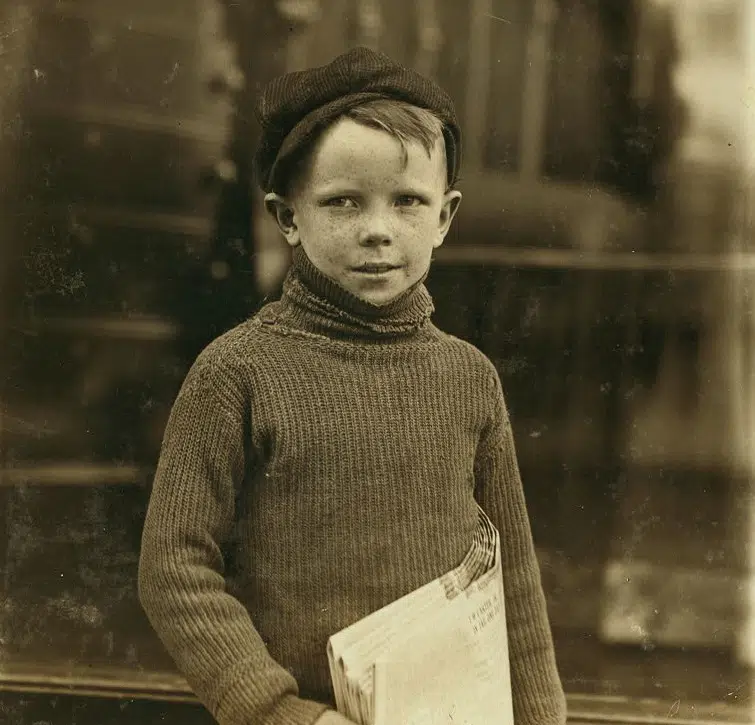

As the wheels of innovation propelled American cities into a new era of urban development, it would test the need for social services in its biggest civic centers. By 1850, nearly 30,000 orphans made up nearly five percent of New York City’s total population. With the troubles of the industrial revolution, however, also came the solution: the introduction of orphan trains.